|

“WITCH DOCTOR OF DARKEST AFRICA AND HIS HOUSE OF FEAR” |

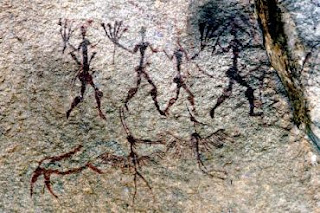

Today I am going Aristotelian on you and throw some Socratic method at you. (Joke) What is the problem with this picture? Does it seem out of place in the twenty-first century? By now you should realize that I understand the three c’s, conversion, commerce and civilization as patriarchal and state derivations. Of course these derivations are culture derivations, which are the result of our original state in paleontology; i.e., “culture is the human nature.”(Sahlins, 103-104) Security is therefore the result of social interaction and the human need to survive that drives humanity to form social groups. In the stories by Henri Lopes of the Congo and Luis Bernardo Hanwana of Mozambique, security and social interaction are explored as inversely related. Is this inverse relationship the result of the culture that is human nature? Does this drive to survive necessarily mean human security is constituted for better or for worse within society? (Sahlins 109) Western history dates the introduction of European explorers meeting with the San, Khoikhoi, and mixed Bantu-speaking Africans in Algoa Bay in the 15th century. Bantu dialects are spoken all over sub-Saharan Africa; the linguistic similarity was not the focus of the first Europeans in the southern part of the continent, id. est. Mozambique. Instead they focused on racial categories that date back to the Arabic medieval epoch when they called sub-Saharan Africa bilâd as-sûdân. “The land of the blacks” offered fertile territory for the three c’s.

The Europeans observed the San, Khoikhoi, and mixed Bantu speakers who lived in kinship residential groups as inefficient because they did nothing to overcome this inefficiency for progress. They were never in a hurry. In the story of the snake, this practice is shown in five different characters’ interactions with domestic animals. Nonetheless, the European idea that the people of the sub-Sahara are primitive is a misconception based on the demotion of everyday labor for consumption that is detached from the familial group. Consumption finds its “self” in an external realm governed by commerce, conversion, and civilization. (Sahlins, 76-77) Individual production within the familial group defines western progress. Production intensifies for the familial group with the empiricism brought to bear by commerce. Indeed, we may as well include conversion and civilization, because, all the stories outside of northern Africa in The Anchor Book are about the disarray of the culture, i.e. human nature.

In Swaziland, the everyday practice of putting out “medicine” to keep away snakes is reminiscent of Hanwana’s story of the black mamba. I witnessed the death of a juvenile spitting cobra in Swaziland and there was nothing magical about it. However, inclined as I am to agree with sociologists and archaeologists about social grouping for survival; I think living in abundance is a human practice, which any human should recognize as our earliest socialization. I am referring, of course, to witchcraft and medicine as we read it in “The Prophetess” by Njabula Ndebele; as it is practiced everyday; it is a cultural practice, whether or not the western reader accepts it. That being said, I want to suggest that traditional, patriarchal and legally governed states are subject to greed and hierarchical societies, even those whose practices are dismissed.

Other stories in our reader, specifically,“The Last Battle’ by Enekwe and Civil War I-VII” by Maja-Pearce allows the reader to wrestle with the “body politic” and how it applied, if ever, to western culture. I would make a joke here, but Conrad’s Heart of Darkness make the disruption of civilization as a result of commerce and conversion not humorous. The laws of consumption drive people to become “on the edge.” But so does subsistence survival; it also suggests how far one will go until conforming to patriarchal, traditional, state-identified realities are too much. Bessie Head’s “Looking for a Raingod” introduces witchcraft and ritual murder. However, this tale fashions itself in an era of droughts, in which the period of “abundance” became less possible. In contrast, Bessie Head’s A Collector of Treasures, writes that “Witchcraft” is practiced but it is impotent because Mma Mabele has to get up and go to work, even when she is sick. Perhaps civilization as it is written by Head needs to be “consumption”. Ultimately what is the body or the soul as read in the short fiction of The Anchor Books of Modern African Stories? Is it having clean water, enough to eat with others, the stories told and being told?

Study Skills

1. Identify the italicized terms. Develop a thesis using the terms and three stories from The Anchor Anthology text.

2. Use the pictures that accompany the lecture to discuss the italicized terms. You must be prepared to read the pictures as texts. This is a writing across the curriculum question that encompasses sociology and anthropology.